AI Hardware Supply Chain Crisis: Enterprise Impact 2026

AI datacenter buildouts are reshaping the hardware supply chain. Enterprise infrastructure costs rising, lead times extending. What you need to know now.

AI NEWSTECHNOLOGY

12/8/202512 min read

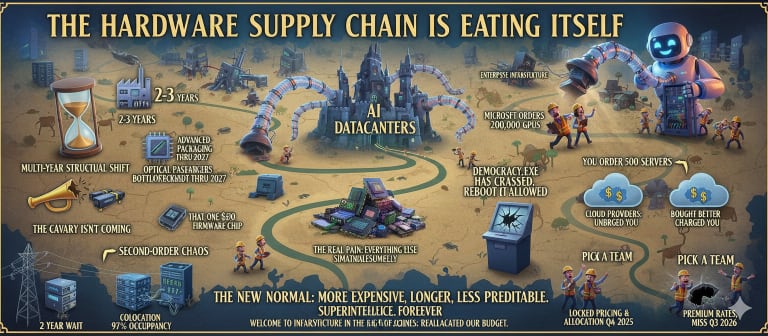

TL;DR: The Hardware Supply Chain Is Eating Itself

The short version for people with meetings in 3 minutes:

AI datacenters aren't just buying more hardware—they're mathematically reallocating the entire manufacturing base. Your enterprise infrastructure is now competing with companies spending $50-300 billion on compute. Spoiler: you're losing.

This isn't a temporary shortage. It's a multi-year structural shift. New fabs take 2-3 years to build. Advanced packaging is bottlenecked through 2027. Optical transceivers will run 40-60% short through 2027. The cavalry isn't coming.

GPUs are the headline, but the real pain is everything else at the same time: 800Gb optics, HBM memory, NAND flash, enterprise CPUs, networking ASICs, and that one $50 firmware chip that delays your entire $100K server deployment.

Hyperscalers define allocation. Enterprises wait in line. When Microsoft orders 200,000 GPUs, and you order 500 servers, guess who gets priority? (Hint: not you.) Democracy.exe has crashed. Reboot not allowed.

Cloud providers didn't dodge this—they just bought better umbrellas and charged you for them. Same supply chain. Same constraints. Different billing model. Your costs go up either way.

Second-order chaos: Power grid wait times hit 4 years. Cooling systems are bottlenecks—colocation at 97%+ occupancy. Your VMware refresh? Lower priority than AI training clusters. The infrastructure that works has become infrastructure that doesn't get upgraded.

If you haven't been planning supply strategy since Q4 2025, you're already behind. The calm enterprises lock pricing and allocation now. The panicked ones pay premium rates and miss the Q3 2026 timelines. Pick a team.

The punchline: This is the new normal. Everything costs more, takes longer, and is less predictable. Forever. Or until the next paradigm shift. Whichever comes first.

Welcome to infrastructure in the age of superintelligence. The machines didn't replace us. They just reallocated our budget.

That was the polite version. Here's what's actually happening

The January 2026 Reset

You haven't seen it on CNBC. Nobody's panic-buying yet.

But you will.

Revised quotes are landing in inboxes like bad Tinder messages. Lead times stretched. Component allocations tightened. Suppliers are calling customers directly—not with press releases, with apologies wrapped in corporate-speak.

Translation: We have less than we promised, and we're very sorry (not really), but also there's nothing you can do about it.

This isn't a supply crunch. It's a structural shift masquerading as a logistics hiccup.

Price increases and lead time extensions aren't isolated events. They're symptoms. The AI megadatacenter buildout is fundamentally reshaping the hardware supply chain. The reshuffling isn't temporary—it's multi-year, cascading, and it doesn't stop at GPUs.

It's like every startup founder's pitch deck, except with significantly more infrastructure collapse.

If you haven't been thinking about supply strategy since Q4 2025, you're already behind. Enjoy that crisis.

AI Mega Datacenters: The Demand Shock Nobody Modeled

Here's the thing about AI infrastructure demand: it's not additive.

It's multiplicative like compound interest, but for silicon shortages.

When hyperscalers commit to building 10 gigawatts of AI compute—and they have, plural—they're not ordering more of what existed before. They're pulling resources from across the entire stack. Simultaneously. Like a vacuum cleaner pointed at the global component supply with the suction cranked to "existential."

GPUs, yes. But also:

Dense networking. A single AI cluster needs 800-gigabit optical transceivers at scale. That's 10–20× the bandwidth of traditional enterprise data centers. Every connection between servers. Every fabric link. Every interconnect in a supercluster. All in parallel, not serial. Kind of like trying to hydrate every person at Burning Man at once—also known as "physically impossible."

Massive storage throughput. Training modern AI models means ingesting petabytes of data. That data lives somewhere—nearline hard drives for cold data, flash arrays for warm. Both are now constrained. Think of it as AI eating through storage the way your coworker eats through the office snacks: relentlessly, without apology.

Ultra-dense power and cooling. A single rack of Blackwell GPUs draws 140 kilowatts. That's not a typo. Most enterprise equipment draws 5–10kW per rack. A single AI rack is 15–30× more power-hungry. Multiply that across a 100-megawatt facility. You're talking about infrastructure that doesn't exist yet—and won't for years.

Spoiler: utilities are thrilled about this. (They're not.)

High-bandwidth memory (HBM). Not regular DRAM. Not even DDR5. Specialized. Expensive. Exotic. The kind of memory that makes DDR5 look like bargain-bin clearance. Micron—the largest supplier—sold its entire 2026 output before manufacturing a single chip.

Let that sink in. The product is sold out before it's made. That's not demand planning. That's the apocalypse with a purchase order.

The demand from hyperscalers isn't competing with enterprise demand. It's resource gravity—a black hole with API access.

Enterprises aren't losing access because hyperscalers are stealing it. Enterprises are losing access because entities with budgets the size of small nations have mathematically reallocated the manufacturing base.

OpenAI and NVIDIA alone are deploying millions of GPUs over the next 18 months. Microsoft is contracting for 200,000 GB300 GPUs across four countries. AWS, Google, Oracle, Meta, Anthropic, xAI—they're all throwing $50 billion, $100 billion, $300 billion at infrastructure. Simultaneously.

When demand from three to five companies accounts for hundreds of billions in annual capex, they don't negotiate for allocation.

They define it. You're just a footnote in the procurement spreadsheet.

Manufacturing Reality: Why Supply Can't Catch Up Quickly

Semiconductor manufacturers aren't ignoring this. They're ramping.

But ramping takes time. And time is the one thing nobody has—kind of like that one developer who "just needs five more minutes" before deploying to prod on a Friday.

Fabs are booked through Q3 and Q4 of 2026. Foundries run at full utilization. When TSMC, Samsung, and Intel say they'll build more capacity, that's not hyperbole. But building a new semiconductor fab takes at least 2–3 years.

You don't start shoveling dirt tomorrow and have wafers rolling in 2026. Physics still exists, despite what venture capitalists believe.

Advanced packaging is worse. CoWoS-class packaging—the sophisticated assembly process for chiplets and advanced GPU architectures—is a structural bottleneck. It won't be resolved for several years. There are one or two players who can do this at scale. They're booked. Expanding capacity requires new equipment, trained labor that doesn't yet exist, and, apparently, divine intervention.

Networking optics? 800-gigabit transceivers will run 40–60% short of demand through 2027. The next tier up (1.6 terabits per second) will be short by 30–40% through 2029.

Blame laser suppliers. Blame the transition to exotic, complex components. Blame geopolitics and export controls on advanced manufacturing equipment. Blame whoever you want—the reality remains unchanged.

Optics, not GPUs, will be the bottleneck that throttles datacenters before the decade ends. You heard it here first. Write it down.

You can't forklift-upgrade a fab. You can't hire specialized semiconductor engineers, train them, and have them productive in six months. You can't build three new laser production lines while fixing the supply of indium phosphide substrates and complex photonic components.

The supply side isn't lazy. It's physically constrained—like trying to get a concrete truck through a drive-thru window.

Storage, Compute, and Networking: Shared Choke Points

Every component in your infrastructure competes with the same supplier base. It's like musical chairs, except the music has already stopped, and hyperscalers have taken all the seats.

NAND and SSD allocation. First time in history that both HDDs and NAND flash are tight simultaneously. Historically, they've been a supply seesaw—one spikes, the other drops, workloads shift. Not anymore.

Hyperscalers' training models need petabytes of data. Some on nearline HDDs. Some on flash arrays. Both are scarce. The seesaw broke. Everyone's on the ground now.

NAND suppliers are sold out of 2026 allocations. Contract prices are rising in double digits. One central NAND controller CEO told industry analysts that NAND supply will be tight for the next ten years.

Not because of permanent undersupply. Because manufacturers have deliberately constrained capex to avoid another oversupply collapse—also known as "we learned our lesson about making too much stuff people actually want."

Enterprise storage teams aren't panicking yet. They should be planning. (They won't. But they should.)

CPU vs. GPU prioritization. Foundries have limited wafers. They're prioritizing AI accelerators—GPUs, TPUs, custom ASICs—over consumer and enterprise CPUs.

What gets priority? H100s. Blackwell. Hopper. Not the Xeons that refresh your general-purpose infrastructure.

The CPU refresh you planned for Q2 2026? Expect delays. Expect allocation controls. Expect manual approval workflows your vendor never told you about—because they're making them up as they go.

Networking ASICs and optics scarcity. I mentioned optics above. The problem goes deeper—like "Mariana Trench with a fiber optic cable" deeper.

Networking controllers—the PHYs, the switches, the adapters—all component-constrained. A single missing NIC delays entire server builds. Optical modules that power east-west fabric traffic between GPUs aren't fungible. You can't swap brands mid-project. (Well, you can, but then everything breaks and your network team quits.)

Why does enterprise gear lose priority?

Because hyperscalers buy in 50,000-unit contracts, they have multi-year LOIs. They work directly with foundries, not through distributors. When a hyperscaler needs silicon, it doesn't wait in a queue.

When an enterprise orders 500 servers, it gets in line behind a company that just signed a $10 billion deal.

Democracy.exe has crashed. Reboot not allowed.

Cloud Providers: Not Immune, Just Abstracted

Azure, AWS, and Google Cloud didn't dodge the storm.

They bought a better umbrella. And charged you for it.

Yes, they're insulated from public allocation shortages—direct relationships with foundries and suppliers. Yes, they absorb price increases faster than enterprises. Yes, they move allocations between regions and SKUs with the flexibility most enterprises dream of.

But the supply chain they're drawing from is the same. They're not getting extra wafers that don't exist. They're not pulling silicon from a parallel universe—despite what their sales decks imply.

They're getting theirs first. Which means everyone else gets theirs later, at higher cost, with a smile and a service-level agreement.

Azure's AI regions and SKUs take priority over general-purpose compute. AWS is selling GPU capacity at premium pricing because it's genuinely scarce. Google is expanding GCP regions aggressively but quietly dealing with the same component constraints as everyone else.

The cloud abstraction hides the scarcity. Your bill goes up. Your timeline slips. Your PM asks, "Why?"

But the supplier bottleneck remains. Cloud providers have leverage. They don't have magic.

Think about that next time your AWS rep tells you "everything's fine."

The Second-Order Effects Enterprises Miss

This is where operational reality diverges from financial forecasts—also known as "where PowerPoints meet physics."

Power availability is now a hard constraint. Not the capacity inside your data center. Utility grid capacity in your region. The stuff nobody thinks about until it's too late.

Colocation facilities in Northern Virginia, Dallas, Phoenix, and the Bay Area are hitting the ceiling. Wait times for new power connections from utilities have stretched to four years.

Four. Years.

Not months. Years. Long enough to start and finish a bachelor's degree while waiting for the utility company to return your calls.

Some utilities require data centers to pay for grid improvements as a condition of service. Others have implemented dynamic pricing, where peak-hour electricity costs 3–5× the off-peak rate.

This isn't friction. It's a physical ceiling on where you can put new infrastructure—kind of like realizing your apartment can't fit a second refrigerator without blowing the breaker.

Cooling density is another ceiling. Traditional air-cooled data centers can't handle 140-kilowatt racks. Direct-to-chip liquid cooling, immersion cooling, two-phase cooling—these aren't nice-to-haves anymore. They're mandatory for AI infrastructure.

Every cooling system adds complexity. Cost. Potential failure points. Dependencies. And the delightful possibility of a coolant leak turning your GPU cluster into a very expensive aquarium.

The global data center cooling market was $10.8 billion in 2025. It's projected to hit $25 billion by 2031. The cooling supply chain is itself a bottleneck. Because of course it is.

Colocation constraints cascade. If the prime colocation facilities in your region are at 97% occupancy (some are sub-1% vacancy), you're not getting cabinet space. You're not getting power. You're not getting cross-connect priority.

Smaller, less-connected facilities have capacity—but at higher cost, worse connectivity, worse redundancy, longer power-up timelines. It's like flying Spirit Airlines when you needed Delta.

Firmware, BIOS, and "small part" shortages. Nobody talks about this because it's unsexy like plumbing at a tech conference.

But when you order a server with a specific combination of CPU, DRAM, NIC, and firmware version, that combination is unique. If the firmware revision isn't available, the BIOS doesn't support a specific PMIC variation, or the power delivery module has a long lead time, you're stuck.

A missing $50 component delays a $100,000 server deployment.

It happens more often than most IT leaders realize. And significantly more often than they'll admit to their CFO.

Roadmap drift toward AI-first products. Every vendor—storage, networking, compute—is designing products with AI in mind first and enterprise workloads second. You know, the workloads that actually pay most of their bills.

New processors optimized for traditional workloads are getting canceled. DDR4 is being phased out faster than demand drops. Older, stable product lines are reaching end-of-life while you still have estates depending on them.

Your VMware cluster isn't getting new hardware any faster. Your storage refresh is getting lower priority. The infrastructure that works has become infrastructure that doesn't get upgraded.

Efficiency theater, complete with analytics!

Who This Impacts First in the Enterprise

Spoiler: not the people you'd expect. (Actually, exactly the people you'd expect if you've worked in IT for more than six months.)

Datacenter services and operations teams feel this first. They're getting the supply calls. They're negotiating lead times. They're explaining to managers why a server refresh that was supposed to complete in Q2 is now targeting Q4 2026—maybe.

They're also the ones who understand that this isn't incompetence. It's market structure. But try explaining "market structure" to a VP who just wants servers.

Storage and backup teams are next. They planned a NAND-forward refresh because flash got cheaper. Now they're locked into long-term contracts at higher prices, dealing with allocation controls, and discovering that some of their planned storage consolidations aren't feasible.

The capacity they need doesn't exist. But the budget was already approved, so good luck explaining that one.

Network engineering is underwater. They need optical modules that won't be available until Q3 2027. They're planning architectures around components that have 9-month lead times. They're designing for redundancy that costs more because optics are scarce.

Also, they're stress-eating. Check on your network team.

Security and compliance programs quietly suffer. Infrastructure refresh cycles slip. Older servers stay in place longer. Legacy operating systems get extended lifecycles by accident—also known as "technical debt that auditors notice later."

This creates problems that surface during the next audit. Cue the angry emails.

Application teams waiting on infrastructure are angry before they even realize there's a supply chain issue. Their performance testing gets delayed. Their deployments take longer. They blame infrastructure.

Infrastructure is actually waiting for components. But nobody cares about that part.

Nobody notices infrastructure until it's too late. Then everyone notices.

But by then, the problem is systemic, not tactical. And you're in a meeting explaining why the thing that was supposed to be done three months ago still isn't done.

Why This Is Not a Buying Panic (Yet)

Here's what this is not: a signal to panic-buy components at inflated prices or take whatever you can get your hands on.

That's the next phase. We're not there yet. (Give it six months.)

Panic buying during shortage cycles historically destroys value. You overbuy at peak pricing. You lock into bad contracts. You end up with excess inventory when supply finally catches up and pricing normalizes.

Some of that will happen. Most enterprises will do precisely this. They'll lose money on it. Then they'll blame procurement.

What you should actually be doing is different: deliberate, forward-looking planning. (I know, revolutionary concept.)

The enterprises that survive tight supply cycles intact are the ones that:

Plan 6–12 months ahead, not 6 weeks like adults with calendars.

Lock in supply commitments early while pricing is still somewhat rational, rather than reactive buys when everything's on fire.

Diversify suppliers and product families instead of betting on a single vendor's roadmap. (Because vendor roadmaps are fiction with bar charts.)

Understand that timing and sequencing matter more than speed.

Have visibility into their own capacity constraints—power, cooling, colocation—and plan infrastructure around those limits, not around hypothetical vendor supply that keeps saying "two more weeks."

Maintain a strategic inventory of critical components, NICs, memory modules, and storage controllers so that a supply hiccup doesn't freeze an entire build. It's like keeping spare batteries. Boring, but effective.

Calm planning beats reactive purchasing. Foresight beats panic.

That's not optimism. That's mechanics. Also known as "doing your job."

The Real Shift: AI Changed the Supply Chain, Not Just the Software

This is the part most executives miss. And it's why this post matters. (Pay attention, this'll be on the quiz.)

AI didn't create a shortage. It created a structural reallocation—like a corporate reorganization, except with silicon.

Billions of dollars worth of capex that would have spread across 100 vendors and 1,000 product SKUs is now concentrated on maybe 20 vendors and 50 core components. That concentration accelerates innovation in those areas.

And starves everything else—the circle of life, enterprise edition.

Your enterprise storage refresh isn't canceled because of a pandemic. It's delayed because NAND production is being redirected to hyperscaler-grade QLC arrays.

Your CPU refresh isn't stuck because of a chip flaw. It's stuck because foundry capacity is allocated to AI accelerators that generate higher margins.

Your networking upgrade isn't bottlenecked because of a design problem. It's bottlenecked because optical transceiver production can't scale fast enough.

This is rational for the vendors. Rationale for hyperscalers. Efficient for capital markets.

Terrible for everyone else. But hey, efficiency!

And it's not reversing in 2026. Probably not reversing in 2027. The capital commitments to AI infrastructure are so massive and the lead times so long that this allocation regime persists for years.

Supply will eventually catch up—new fabs, new packaging lines, expanded optics production. But catch-up means 2028, 2029, maybe 2030 for some components.

That's the January 2026 reset. Not emergency shortages. Not panic prices.

Just the new normal: everything costs more, takes longer, and is less predictable.

Forever. Or until the next paradigm shift. Whichever comes first.

Welcome to infrastructure in the age of superintelligence. The machines didn't replace us. They just reallocated our budget.

This is Part 1 of a 3-part series on the AI hardware supply chain problem—how it spiraled, why demand broke every forecast we trusted, and why “just wait it out” stopped being a strategy.

If Part 1 is the diagnosis—how we got here and why the pressure keeps building—then Part 2 is where we confront the uncomfortable reality: this isn’t going to fix itself, and hope is not a strategy.